by SARA CHERNIKOFF, THERESA COTTON, ALEXANDRA MACIA and SEAN McGOEY

In the eyes of parents, Montgomery County Public Schools have major issues

by Alexandra Macia

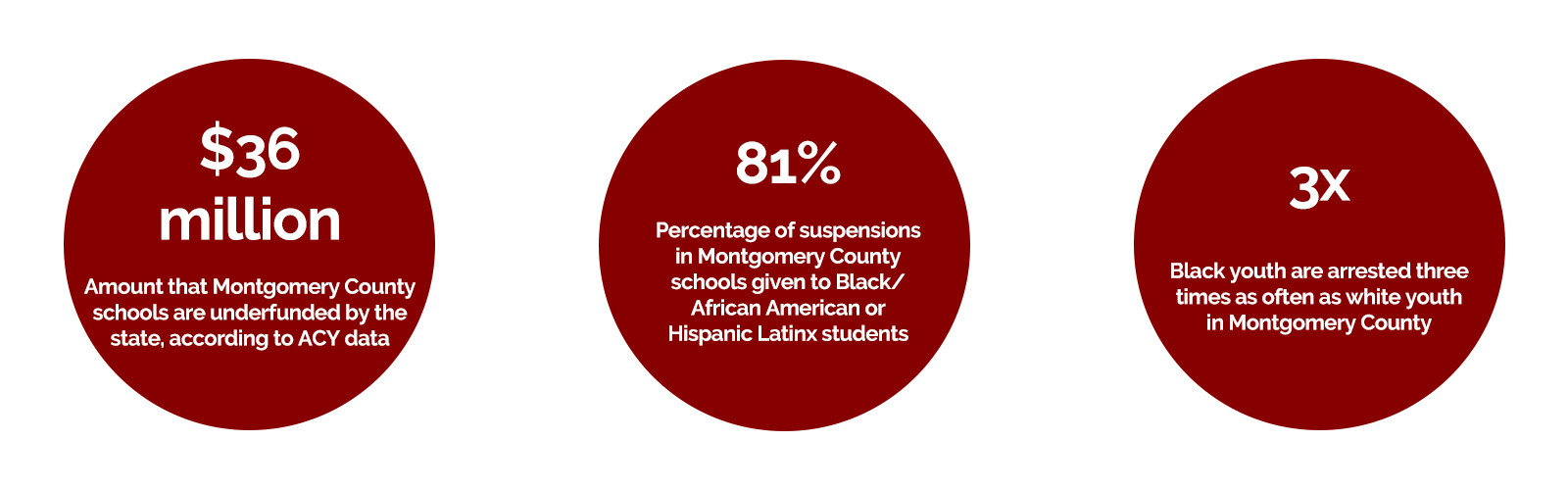

Montgomery County public schools have been struggling with large disparities in race, funding and disciplinary action.

There are 165,267 students enrolled in MCPS, according to the school system. The school suspension population is racially divided – over 80% of suspended students are African American or Hispanic/Latino, while only 12% are white. In addition, black youth are arrested three times more often than white youth in Montgomery County.

Furthermore, the state underfunded Montgomery County’s schools by $36.2 million in the 2016-2017 school year, according to data compiled by Advocates for Children and Youth.

For the parents of MCPS students, facts like these can be extremely alarming. Some parents highly involved in advocating for education reform commented on their thoughts about what issues are most relevant in Montgomery County’s school system.

When Winston Churchill High School Parent Teacher Student Association President Carla Morris was appointed to her position, she had one planned focus – but that focus quickly shifted once she began her term. According to Morris, a major issue in the school system is that there are not enough guidance counselors for students, leaving students unable to receive adequate mental health attention.

“I was going to focus on (the) achievement gap and equity disparities in schools here but instead I hit the ground with vaping, heroin use, and opioid handouts, which ties right into mental health challenges,” said Morris. “To me those are the two big issues – and also, frankly, also safe use of cell phones in classrooms, because there is a lot of problems with kids who are not learning and just playing.”

Another issue that Morris emphasized was the need for smaller class sizes for students; class sizes negatively correlate with the amount of attention students are receiving from their teachers.

Mitra Ahadpour is a parent of two boys who already graduated from MCPS schools and a daughter who is in the ninth grade. She is currently the principal deputy director for the Federal Drug Administration and is running to be on the Board of Education.

In the past, Ahadpour worked on the initiative that made Montgomery County the first smoke-free county in Maryland. The issue of prevalent drug use and vaping is one she is still very passionate about and has mentioned as a topic in which she would focus on her in her campaign.

“I think there is a lack of awareness from MCPS and the Board of Education on what we are seeing on the ground (in schools),” said Ahadpour. “We are having a rampant use of vaping in the classrooms, bathrooms, hallways, gym and in the buses. There is a lack of education and awareness and no enforcement.”

According to Ahadpour, she decided to run for the Board of Education because of her passion towards making change in the education system. She believes that her past attempts have “fallen on deaf ears.” As a first-generation immigrant, Ahadpour believes that all students are capable if given the right foundation for success.

“MCPS spends more money on their school systems than most districts in the United States but we are not improving our student outcome,” Ahadpour said. “Why is it that the SAT scores have gone down again this year? It's because we are not doing it correctly. We don't put in the effort to have a student approach.”

Byron Johns, a father of students enrolled in MCPS, is an education advocate and the chair of the Montgomery County NAACP chapter’s Education Committee Parents Council. One of his main concerns lies in the implementation of school resource officer programs, which place police officers in local schools.

“We’re concerned, especially black and brown parents, because our communities have a troubled relationship with the police,” said Johns. “It stems from many years of how the police have been used to suppress communities of color.”

According to Johns, many members of the police force come from outside the community they are patrolling, which can be seen as a threat to young black males and black communities.

“When you bring that into the school, you have all the ingredients for fast tracking school to prison pipeline,” said Johns. “We don't want the school to turn into a hunting ground for police officers because you know that the kids will go to the school. You create a very hostile school environment when you are pulling kids out or looking to arrest kids in the schools.”

Montgomery County is well-funded, but still struggles with racial disparities in discipline

Source: 2020 Maryland County Data Sheets from Advocates for Children and Youth.

Montgomery County parent is troubled by inconsistencies in school system

by Alexandra Macia

Potomac resident Stacey Shenker has a decade of experience with public schools in Montgomery County, with children enrolled in MCPS schools at every level: Winston Churchill High School, Herbert Hoover Middle School and Beverly Farms Elementary School. When asked what she believes to be the most pressing issue within MCPS as a parent, her response is simple.

“I think that there is a difference between what goes on in the buildings and what goes on in the administration,” said Shenker. “The biggest issue in the school system right now is the lack of consistency across the schools.”

Curriculum, course offerings and even teachers within the school make up some of the major inconsistencies that affect both parents and students, according to Shenker, who said that two third grade teachers may differ on as fundamental an issue as whether to give homework.

“The teachers interpret curriculum differently,” Shenker said, “which leads to discrepancies in what's happening in one school versus another.”

Shenker said that while one of her children was at Potomac Elementary School, the school was a “no homework” school. The former principal had given parents research on why homework was not appropriate for younger levels and had compelling arguments that made her comfortable with this decision. Although, some parents disagreed and so the school began giving homework, but didn’t count it for credit.

“It would have been fine if the entire system had the same approach,” said Shenker. “(But) when the kids got to middle school they didn't have the same study skills as their peers... It was a tougher adjustment for them than for their peers from other schools who had regularly been doing homework, were expected to turn it in and learned how to prioritize their time.”

School Resource Officers

Another controversial issue within MCPS has been the implementation of school resource officers, sworn law enforcement officers assigned to work in schools. While members of the county council have advocated for more trained SROs in schools to help de-escalate violent situations, many parents are concerned that SROs unjustly target students based on race.

Shenker said that the word she would use to describe how she feels about SROs would be “conflicted.”

“It is very hard to say because every child is different and what is reassuring for one child and family may be anxiety-inducing for another child and family,” said Shenker.

Shenker said the police presence itself doesn’t bother her as a parent.

“I wouldn't say I find it reassuring,” Shenker said, “but I also wouldn't say that it makes me feel anxious.”

Shenker had a bad experience with her son at another school in which he was threatened and attacked on multiple occasions. She believes the SROs could have positively impacted her son's experience.

“It would have been a great reassurance to my son to have had a police officer in the school, but also our school security was on top of it and more than capable of handling the situation,” said Shenker.

While Shenker wouldn’t have an issue with SROs at the high school or middle school level, she said she would draw the line at police officers in elementary schools.

Busing

Finally, Montgomery County has been exploring redrawing school districts, which has brought up the possibility of busing students to schools that are farther away from their homes. According to Shenker, her past experience with long bus rides has led her to be against the proposals.

“Part of the reason we left Potomac Elementary School was because our bus rides to go 1.9 miles to school from the bus stop took 43 minutes,” said Shenker.

Shenker said that in her area, they don't have community bus stops, but stops that serve only one family. Therefore, buses have to make 14-16 stops during the ride, which makes it extremely long. Many parents drive their kids to school as a result, so their kids can avoid taking the bus, which makes carpool lines very long.

One of the main reasons Shenker said she chose to live in Montgomery County was because of the public school system, but she believes spending an hour a day each way on the bus is unhealthy for all kids and gets in the way of many things including homework and extracurricular activities.

If the proposals ever went through, Shenker said, “We would leave the county without a doubt.”

Nearly three-quarters of county suspensions are given to black and Hispanic students

Percentage of in-school suspensions by race in Montgomery County schools, 2017-18 school year

Source: Maryland Department of Education

Activists for racial justice examine public school discipline in Maryland

by Theresa Cotton

Defenders of the First Amendment and community activists in Montgomery County seek to end racial inequality in public schools by examining strict discipline and exclusionary policies that police students rather than foster learning.

These groups actively work to educate parents, teachers, and community members on the experiences that students from minority backgrounds have with disciplinary policies that can dramatically harm their development and future success. Exclusionary policies alter enrollment demographics in public schools, leaving some students feeling isolated and underrepresented.

“The first step is education,” said Sue Udry, executive director of Defending Rights and Dissent, an organization that has worked with the Montgomery County Civil Rights Coalition to connect students with activist groups and resources in their community. “Young people can take an analytical eye to how the criminal justice system is impacting their own community, particularly in high schools, the presence of School Resource Officers.”

Community activist leaders want students to become aware of beneficial resources and forums that can facilitate student-led programs or important conversations between parents and school administrators. Some students do not receive fair treatment or appropriate counseling when they need it most, which can help fuel major issues such as the school-to-prison pipeline.

According to Montgomery County’s School-to-Prison Pipeline report, black and Latinx students were more likely to receive an out-of-school suspension or expulsion than white students for the same offense. Zero tolerance discipline policies contribute to declining enrollment rates and an increase in students becoming incarcerated at a young age.

The presence of school resource officers can impede students’ academic success based on the lack of training offered to teachers and absence of appropriate behavioral support programs for students.

“Teachers need to be given much better training on how to manage students in their classrooms in a way that supports their educational goals and understand that they are young people,” Udry said. “There’s just a huge deficit in administrators’ understanding that these students are children and should not be treated like criminals if they act out.”

Theory models such as the Countering Violent Extremism Model and other threat-assessment models have been developed for teachers to accurately differentiate between threatening and non-threatening behaviors, but even these models are flawed and are influenced by racial stereotypes. The models include making assessments based on individual and situational indicators such as a student's transition to the US or appear to be “at-risk of becoming violent”.

Robert Stubblefield, an activist for racial justice and program organizer, experienced unequal treatment first-hand during his time in public school. In a January article for Maryland Matters, Stubblefield recounted several instances of inappropriate treatment fueled by prejudice, ignorance and classist attitudes, which can make it difficult for students to find support or discover resources that can help them achieve academic success and overcome individual challenges.

“My advice for students facing this kind of adversity is to continue to pursue their educational interests and contribute to activist groups that serve their community,” Stubblefield said.

Montgomery County teachers' union seeks reforms to public school system

by Alexandra Macia

The Montgomery County Education Association is one of the largest local affiliations of the National Education Association, with about 14,000 members. Over 95% of Montgomery County teachers are members of the union, according to MCEA Vice President Jennifer Martin.

Martin's role includes being a member of the board, working to help with their initiatives, working closely with members about what they want to see done and managing the peer assistance and review program within Montgomery County’s Public Schools. MCEA works on a variety of initiatives and problems within Montgomery County’s public school system with a focus on ensuring that the organization is member led.

“We are as strong as our members, so our union is about helping people to organize that power and work out solutions within their schools, but also to take on larger issues that affect all of us in public education,” said Martin. “We see ourselves as bargaining for the common good not just for traditional issues of wages and benefits, but also really using our negotiation opportunity as a time to think about what our students and communities need from the public education system.”

While MCEA primarily advocates for teachers’ needs, they advocate for students as well, because as Martin puts it, “students' learning conditions are our working conditions.” One of the main things MCEA is working on right now is contract negotiation for teachers. A main focus of those negotiations includes the topic of timing. MCEA is trying to make sure that teachers have the time to do the best they can in their work.

“The structure of the day leaves little time for people to do their own individual planning and to address the particular needs of their students,” Martin said. “We are trying to make space for that and primarily where we see this being an issue for students is we do not follow state guidelines in Montgomery County for art, music, P.E. and technology coursework for elementary kids.”

"Our job is to meet the needs of the children we receive and to do our very best to bring them the education that they need ... Kids may not come with the same background, but they all come with tremendous capacity to learn."

-Jennifer Martin, vice president, Montgomery County Education Association

MCEA has had a number of successes over the years: keeping standardized testing in proportion for students, ensuring that special education and English-learner students receive necessary resources and ensuring that teachers' professionalism is honored and their voices are heard.

“We have been proponents of having opportunities of innovation in schools by creating inclusivity and honoring diversity. We were the champions of having equity training for our teachers,” said Martin. “We have also been at the forefront of a lot of the more innovative and progressive approaches to educating children and students.”

Teachers face many challenges, so MCEA relies on strength in numbers.

“The pressures of the teaching life are intense and the needs of our students are often beyond what an individual teacher can address on her or his own,” said Martin. “So, the power of union is in being able to bring people together to identify those needs and then to press for the resources and solutions that are going to work, so that we are not isolated in our classrooms and are systematically addressing those problems and challenges.”

Martin, a teacher since 2002, said that her concerns about the lack of educators’ voices in the system made her want to join the union – where she felt teachers' voices had more of a chance at being heard.

“My engagement in the union was because I wanted to promote public education, to be a spokesperson for the profession and to have the opportunity to connect with the people who make decisions about our work, but may not understand the nature of our work,” said Martin.

Based on Martin's experience, the issues teachers face are simply a question of time. Many teachers are teaching about 150 students and trying to understand their needs in order to help them reach their full potential. The key as a union, then, is to ensure that every school and child has access to excellent educators.

Martin has taught students from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. In her experience, there are different challenges, struggles and successes that students from different environments face. Martin currently teaches at Takoma Park Middle School, where her students are English language learners at the lowest level. When she taught at Wootton High School, her students were AP and honors students coming from very comfortable backgrounds.

“The struggle for teachers is real in every school across the country,” Martin said. “Our job is to meet the needs of the children we receive and to do our very best to bring them the education that they need and to help them fulfill their potential. Kids may not come with the same background, but they all come with tremendous capacity to learn and I think that Montgomery County teachers recognize that.”

Kirwan Commission initiative sparks debate over Maryland education system

by Alexandra Macia

More than 60% of Maryland’s graduating high school seniors can’t read at a 10th-grade level or pass an Algebra 1 test, according to the Baltimore Community Foundation. The Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education, also known as the Kirwan Commission, is trying to fix that along with many other issues in the education system.

The commission, an initiative looking to implement education reforms in the state of Maryland, is focused on raising teachers’ salaries, improving working conditions in schools, providing students with more support and expanding pre-kindergarten funding. Monday, Feb. 17, members of the commission met at a hearing in Annapolis to discuss implementing legislation in regards to the commission's recommendations.

Chester Finn, who has worked in education policy for decades, was a member of the commission during the period in which the recommendations were developed. According to Finn, while a diverse set of issues are touched on in the report, all of the issues mentioned intersect.

“I think the report does an excellent job of laying out the shortcomings in Maryland's present education system,” said Finn. “The low test scores, the number of people who don't graduate, the number of people who graduate without being ready for anything that follows, the generally mediocre performance of the states K-12 education system – that is all laid out in the early part of the commission report.”

In a recent interview with Montgomery Community Media, county council member Craig Rice, D-2nd, a member of the commission, voiced strong support for the commission's recommendations.

“At some point, education plays a key role in the social ills that we experience in our community,” Rice said. “If you care about health disparities, if you care about crime, if you care about all the negative ill that we see in our community, you should invest in something like the Kirwan Commission’s recommendations.”

Another major goal of the commission is to update the funding blueprint for schools in Maryland. While the commission does have a lot of support, it also is facing a lot of criticism due to the large amounts of funding in which it is proposing and failed previous attempts at education reform in the past.

Janis Sartucci, a writer for the Parents Coalition of Montgomery County, is unsure how the commission will differ from previous failed efforts at reform.

“For as long as we have been tracking the school system, every year is a budget crisis,” said Sartucci. “It is a recurring theme that there is the next best thing that will solve all education ills, and all we need is tons more money; and somehow, every time we go through this, it doesn't happen.”

Montgomery County disciplinary policy

by Sara Chernikoff

Montgomery County Public Schools outlines a guide for administrators to follow when significant disciplinary action-suspensions, which involve students being excluded from their regular school program for no more than 10 days, and expulsions, which exclude students for 45 days or longer-must be taken against students. But though the guide is direct and detailed, application of these rules is often far from clear.

The school system says that its disciplinary actions reflect a “restorative philosophy” that gives students opportunities to learn from and correct their mistakes, and to restore relationships that are disrupted by their conduct. But the county fails to define restorative disciplinary action in detail, describing it as “(focusing) on repairing harm to the community through dialogue that emphasizes individual accountability” and “(helping) build a sense of belonging, safety, and social responsibility in the school community.”

Furthermore, though long-term suspensions and expulsions are intended to be used only as “last resort options,” they are not prohibited for students as young as pre-kindergarten (though the policy discourages suspending or expelling students so young).

Montgomery County has also been criticized for their use of isolation rooms to punish misbehaved students. The school district reported to the Department of Education 723 cases of secluding misbehaving students, most often special education students, in the 2017-2018 school year. Although it is impossible to know the full use of restraint and seclusion in schools because many school systems don’t keep record.

Physical restraint can mean anything from holding a student's arms to pulling their hold body down. Restraint may also be done with a device such as straps or through medication. Seclusion rooms and spaces vary between school districts, but their purpose is to keep a student in an isolated space, preventing them from leaving.

According to county policy, physical restraint and seclusion is not allowed within the school district unless there is an emergency situation and use of seclusion/restraint is necessary “to protect a student or other person from imminent, serious, physical harm after less intrusive, nonphysical interventions have failed or been determined inappropriate.” There is no federal policy governing how seclusion rooms can be used.

In an interview with Bethesda Magazine, Denise Marshall, executive director of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates – an advocacy group focused on protecting the rights of students with disabilities – called for lawmakers to ban any use of seclusion rooms, even in extreme circumstances.

“To the kids to whom that happened, it’s significant," Marshall said. "Locking someone alone in a room from which they can’t exit is known to be a form of torture, and isolation is traumatizing and it’s harmful to young children.”

In order to determine what type of disciplinary action is taken against a student, their age, previous misconduct, cultural and linguistic factors, circumstances surrounding the incident and other aggravating circumstances are considered. Most of these factors are extremely vague in their language and definitions. The county also fails to address a correlation between identity and the likelihood disciplinary action will be taken against a certain demographic of students, although research and data show a connection. County policy also fails to identify vulnerable students who may be more severely punished compared to his/her classmates.

The school is required to ensure “minimum education services” are provided to students during their suspension meaning, they are able to complete academic work they miss during the suspension period without penalty, but the policy is left open-ended for individual administrators to interpret, and there is no accountability outlined in the policy on how to measure the success of the “restorative discipline philosophy.”

Montgomery County school facts

Student enrollment

162,680

Student demographics

Students receiving free or reduced lunch

35%

Annual budget

$2.59 billion

Schools and centers

206

Employees

23,857

Key figures

- MCPS Superintendent: Dr. Jack Smith

- School Board Chair: Shebra L. Evans

- Student Board Member: Nate Tinbite (John F. Kennedy)

High schools in Montgomery County

- Bethesda-Chevy Chase (Bethesda)

- Montgomery Blair (Silver Spring)

- James Hubert Blake (Silver Spring)

- Winston Churchill (Potomac)

- Clarksburg HS (Clarksburg)

- Damascus HS (Damascus)

- Thomas Edison HS of Technology (Silver Spring)

- Albert Einstein (Kensington)

- Gaithersburg HS (Gaithersburg)

- Walter Johnson (Bethesda)

- John F. Kennedy (Silver Spring)

- Col. Zadok Magruder (Rockville)

- Richard Montgomery (Rockville)

- Northwest HS (Germantown)

- Northwood HS (Silver Spring)

- Paint Branch (Burtonsville)

- Poolesville HS (Poolesville)

- Quince Orchard (Gaithersburg)

- Rockville HS (Rockville)

- Seneca Valley (Germantown)

- Sherwood HS (Sandy Spring)

- Springbrook HS (Silver Spring)

- Watkins Mill (Gaithersburg)

- Wheaton HS (Silver Spring)

- Walt Whitman (Bethesda)

- Thomas S. Wootton (Rockville)